Why global warming doesn’t matter so much to financial markets

18 October 2023Market pricing is too short term to be affected by global warming to the extent we’d like, for as long as carbon remains unpriced

A number of reports have recently appeared stating that economic and financial models severely underestimate the potential impacts of climate change.

Loading the DICE against pension schemes launches a full-frontal attack on the economics profession, accusing it of systematically and enormously underestimating the economic damages from climate change in a way that is inconsistent with climate science and fails a common sense “smell test”.

Researchers from Oxford Economics recently published a paper highlighting negative, non-linear impacts of temperature change on economic growth, leading to potential reductions of 30-50% in projected global output for warming of 2 to 2.6C.

Even the normally conservative actuarial profession got in on the act with a provocative paper called The Emperor’s New Climate Scenarios, stating that many climate-scenario models in financial services are significantly underestimating the economic impacts of climate risk.

All of these papers take issue with projections from so-called integrated assessment models that put economic losses from climate change at around 20% of GDP at warming of 4C. They contend that such projections provide an unrealistically sanguine view of the impacts of climate change due to a number of flaws, including: extrapolation of damage functions from current geographic cross-sectional temperature differences to trends over time; estimation of damages using insufficiently granular geographic cell sizes, resulting in underestimates of weather variability and damages; failure to take account of non-linear feedback loops and tipping points; and the failure to differentiate between mean temperature effects and precipitation effects (the latter of which holds the potential for significant negative effects in northern developed markets).

These papers do not provide precise alternative projections, but instead encourage use of a much broader range of scenarios for economic impact than is currently implied by commonly used scenarios such as NGFS. However, it is clear across the three papers that they envisage the use of scenarios that might put economic losses at 50% of GDP by 2100 or even more, relative to the scenario in which there is no climate change.

These analyses of massively negative outcomes appear to sit uncomfortably with the relatively modest projections of climate impact arising from central bank stress tests and portfolio return estimates from financial institutions and pension funds. Trust et al (2023) note that a sample of financial institutions shows long-term portfolio return differences of no more than 120bp per annum between orderly transition and hot-house scenarios, and often much less. Keen (2023) notes examples of pension funds and consultants attributing negligible differences in portfolio returns under different climate scenarios. Climate stress testing by the ECB and the Bank of England found that potential capital impacts from global warming were perfectly manageable. The apparent disconnect between severe climate impacts and modest market impacts causes the authors to urge institutional investors, banks, and regulators to up their game and recognise the severe risks embedded in financial portfolios.

Discounting and the disconnect between markets and global warming

Such a disconnect between these relatively mild projected economic impacts and the severity of consequences predicted by climate science leads some commentators to the conclusion that the market faces a moment of reckoning: a “Minsky moment” when the impending climate disaster is priced into assets causing write-downs, portfolio losses and system-wide financial stress. Keen (2023) states that “…a wealth-damaging correction or “Minsky Moment” cannot be ruled out, and is virtually inevitable.” As a result, financial institutions, asset owners, and regulators are urged to develop more realistic (and pessimistic) stress tests and scenarios.

The point of this article is not to adjudicate on the debate between climate science and economics. For what it’s worth, I have a lot of sympathy with the idea that economic models are underestimating the impacts of climate change for all the reasons outlined above. I was largely persuaded by Stern, Stiglitz and Taylor’s critique of Integrated Assessment Models. I am unable to be comfortable about the economic or societal impacts of a rapid increase of 4C in global mean temperatures. This is not just because of my reading of the climate science. More fundamentally, how can we possibly be confident that we can deal with global temperatures at a level that has not been experienced during the time humans have been on the earth? The consequences are inherently unknowable and prudence dictates that we should act.

Instead, the purpose of this article is to explain why it is quite possible, with complete consistency, to be very worried about the long-term impacts of global warming but also quite sanguine about its effects on financial markets even in the medium term. The reason is so basic that it is almost embarrassing to write an article on it, but it seems to be a factor that is regularly underestimated. That factor is: discounting.

How discounting affects the way global warming affects asset prices

To help illustrate the point, I’m going to use a very simple example based on Valuation 101 principles.

Consider an investor in a broadly diversified global portfolio. Suppose that the portfolio produces dividends of 100. In my very simple model, we can value the portfolio based on a discounted dividend model. We need to know the rate at which the dividends will grow in real terms, and we need a discount rate. For the discount rate I’m going to assume 5% pa real discount rate, broadly corresponding to the long-run real return on global equities over long periods.

We will look at the valuation of the portfolio under the following scenarios:

As a simplifying assumption we’ll assume that dividends on the portfolio and global GDP grow at the same rate. Here I’ve assumed that the economy grows at 2% pa in real terms in perpetuity in the absence of climate change. Next, I assume that the market is pricing a scenario in which some costs are incurred to get climate change under control, which slows growth slightly during a transition period up to 2070, but ultimately the efforts are successful and the economy re-emerges and continues to grow at 2% pa thereafter. This is a relatively optimistic scenario, where global warming has impacts, but they are neither too severe nor too long-term. This seems broadly consistent with what the market is currently assuming.

Next, I define a Stagnation scenario where growth falls towards 1% pa as climate effects worsen, but they are ultimately controlled and the economy continues to grow, albeit it at a lower rate than historically. Finally, I have a Meltdown scenario, where climate change is ignored in the short-term, so growth is in line with the No Climate Change but thereafter plateaus and starts to decline. These are back-of-the-envelope scenarios, purely for illustration of my argument. The detail does not matter too much for what follows.

Also shown is the reduction in 2100 GDP relative to the No Climate Change scenario. Stagnation and Meltdown result reduction of around half to three quarters of GDP, which is a severity of impact consistent with that indicated in the papers discussed above.

The trajectory of GDP and dividends under the scenarios and over time is illustrated below.

Under the Meltdown scenario, the economy is smaller in real terms in 2120 than it is today. It is clearly a disaster scenario. Somewhat better, but still pretty bad, is Stagnation.

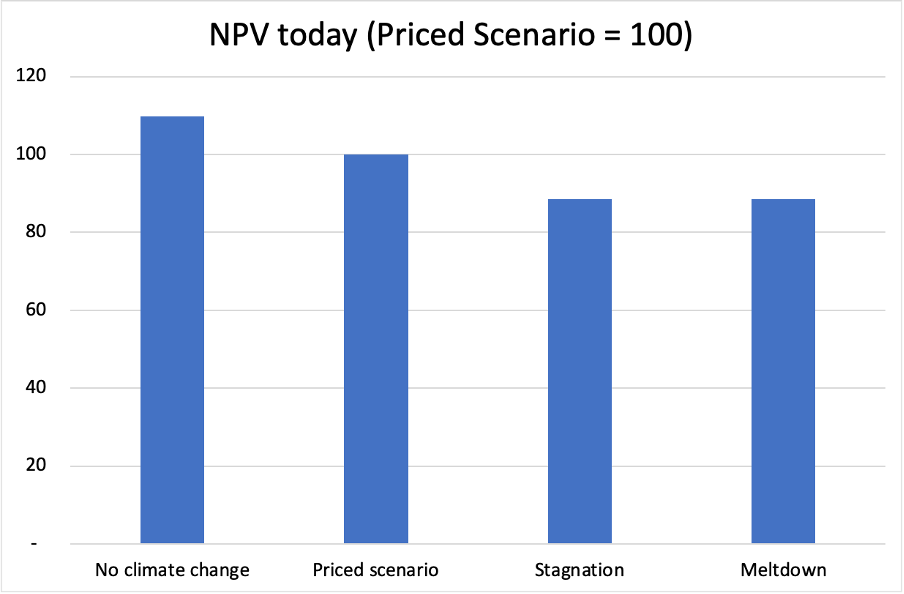

Now let’s turn to valuation, carried out using a simple discounted cashflow approach with our 5% real discount rate. The chart below shows the net present value today of the portfolio under the four scenarios. The valuations are normalised so that the Priced Scenario is set at 100.

Compared with the Priced Scenario, the Stagnation and Meltdown scenarios are only valued at 10% less, and this despite the Meltdown scenario resulting in destruction of nearly three quarters of GDP by 2100 relative to a No Climate Change scenario! This is a relatively modest portfolio value difference: the Vanguard Total World Stock ETF fell by 10% or more over three separate periods during 2022. Surprisingly, Stagnation and Meltdown have the same valuations. The slightly higher short-term dividend growth in the Meltdown scenario counterbalances the longer-term relative disaster of this scenario. This is the effect of discounting, which ascribes much more weight to the near term than the long term.

Impact of climate scenarios on portfolio returns

What about the impact on portfolio returns? This will depend on the timeframe over which the market valuation trends to the fair valuation. If we assume that the starting market price is in line with the Priced Scenario, we can look at the impact on returns over different time periods. In the table below, for example, “Fair value reflected by 2030” means that market valuations have, by 2030, moved from an initial valuation based on the Priced Scenario to a market valuation in line with either the Stagnation or Meltdown fair value, as appropriate. Total returns are then measured from the initial portfolio value today to this realigned value over the period to 2030. The corresponding analysis applies for the 2050 and 2070 timeframes.

If valuations take quite a long time to realign to the Stagnation or Meltdown scenario, then the impact on returns is pretty modest. Returns to 2070 are reduced by less than 100bp in both the Stagnation and Meltdown scenarios, not so different from the examples from financial institutions highlighted in the papers mentioned earlier. If realignment happens more rapidly, by 2030, then consequently the impact on returns is greater, with an impact of more than 200bp per annum. However, by virtue of applying over a smaller period, this impact on portfolio valuations is, in aggregate, not so large.

Minsky Moment?

A different way of looking at the same data is to look at the impact on valuations if markets suddenly come to recognise how bad the future really is. In such a so-called Minsky Moment, the market suddenly takes on board the more gloomy economic outlook due to global warming, resulting in a rapid market repricing. The chart below shows how the fair value of the portfolio moves over time based on the difference scenarios.

We can model a Minsky Moment by looking at what happens if valuations suddenly change from being based on the initial Priced Scenario to either the Stagnation or Meltdown scenarios at different dates in the future. In essence this involves a sudden drop in portfolio value from the Priced Scenario line to either the Stagnation or Meltdown line. The results are as follows:

If the Minsky moment happens in 2030, the impact of a valuation correction is relatively modest, at less than 15% of portfolio value, well within the range of movements within a normal year. The correction only starts to become really severe if realisation is postponed until 2050, which seems implausible since by that time actual economic growth would already have underperformed that in the Priced Scenario for two decades. A 2070 correction to the Meltdown scenario is severe, but is also a very extreme scenario. Investors would need to have ignored the negative news about global warming for 40 years before suddenly waking up to reality in 2070.

Of course markets can overshoot and initial falls could be worse than these fair value estimates. There may be pockets of financial markets, or particularly exposed institutions, that come under severe stress. On the other hand, these are severe scenarios and the market may only apply partial weight to them. Moreover, markets would likely drift to the realisation of the impacts of global warming over time rather than incorporate the bad news in one go. But overall, this simple example shows how the impact of discounting, and the consequent inability of markets to look more than a couple of decades ahead, means global warming will likely have much less impact on financial markets than we might expect or, indeed, wish.

Nothing to worry about?

Does this mean that global warming is nothing to worry about? Absolutely not! Our current trajectory is putting us well into red-alert territory and we are fast approaching the point where we will need to be lucky to avoid devasting impacts for, at least, significant segments of the world’s population. Global warming is an unexploded bomb sitting underneath our society and way of life.

But global warming, at least in the short to medium term, seems unlikely to be a bomb sitting under financial markets. So financial markets, left to themselves, will not defuse it. What this simple analysis shows is that financial markets, and in particular equity markets, will likely not, in aggregate, feel the effects of the looming climate crisis to a very significant degree for decades. (But of course the sector and company specific effects will be felt keenly and much earlier based on the trajectory of global warming itself, the regulatory response from governments, and what this means for winners and losers - but this change and disruption is a constant feature of financial markets down the ages.)

Indeed the bigger risk to markets in the short to medium term would be an unexpected and highly assertive regulatory intervention pricing carbon at a high level, implicitly or explicitly. However, it seems unlikely that governments will voluntarily impose carbon regulation at a pace and severity that of itself induces a market collapse and financial crisis. Indeed, as the effects of climate change get worse, there is a risk that adaptation efforts, with pay-back periods of years, are politically more attractive than mitigation efforts, with pay-back period of decades. The inevitable policy response is not inevitable.

We need to stop pretending that investors are ignoring potential catastrophe and that they would act to stave off epic losses if only they recognised them. We need to stop complaining that bank stress tests are inadequate because their results don’t reflect our sense of impending doom.

Instead we should be honest with ourselves. The impact of global warming on aggregate market valuations will likely be less than many expect, or want to believe, well into the medium term. And in the near future, almost certainly less than other potential risks like recession in the US, slowdown in China, conflict between the US and China, the war in Ukraine, and conflict in the Middle East, all of which will have much shorter-term impacts.

Left to themselves, financial markets will not take notice of global warming until it’s too late. Unless we force them to. Implicit or explicit carbon pricing through regulation, taxation, subsidies, and product standards is the only meaningful game in town. Where these lead, markets will quickly follow. But don’t expect markets to make the first move.

The anti-ESG backlash may have an unexpected benefit for European index fund managers